Think you can be dishonest without displaying any tell-tale signs? Think again. Our bodies simply cannot lie

Unlike Pinocchio, our noses do not get longer when we lie, but there are a host of other reactions that could suggest we are being far from honest.

Yes, just like in spy movies, the polygraph (commonly known as a lie detector), can indeed be beaten, even if it is incredibly difficult to do so in real life.

But thanks to artificial intelligence (AI), interrogators could soon have a new tool that can detect inevitable and fleeting clues our bodies leave behind when we aren’t being honest, regardless of how hard we try to control our emotions.

Tell-Tale Indicators

The fact that our bodies tend to react in certain ways that could betray our false intentions is well documented. After all, polygraphs were built for the very purpose of picking up some of these reactions, or Tell-Tale Indicators (TTIs).

What are some TTIs? For starters, there’s body language, which can be easily observed using the naked eye.

Have you ever noticed someone saying yes but shaking his head instead of nodding? Such non-congruent gestures could be one major sign that the person isn’t telling the truth.

Another example of a TTI related to body language is excessive fidgeting, which could mean looking down at one’s nails, shaking one’s feet or licking one’s lips.

And then we have physiological signs, such as sweating as well as a spike in heart rate and blood pressure, all of which suggests that someone could be nervous or lying. These are the TTIs that the polygraph can identify.

But as mentioned, the polygraph isn’t fool proof.

“Practising deep breathing to keep relaxed may help to avoid triggering an unwanted response. Suspects could also tense up to confuse baseline measurements,” shared Shaun Wee, an engineer at HTX’s Biometrics and Profiling (B&P) Centre of Expertise (CoE).

“However, experienced examiners will know when someone is trying to manipulate their physiological responses. Examiners can also detect practised responses aimed at gaming the system. So, while it may be possible for some individuals to manipulate the results of a lie detector test to a degree, successfully ‘beating’ the test is extremely challenging.

The polygraph can pick up changes in one’s blood pressure and heart rate, both of which could indicate that a person is lying.

Micro-facial expressions

Although seasoned criminals can take measures to calm themselves and beat the polygraph, there is growing evidence that suggests there is another TTI that is difficult to tame – Micro-Facial Expressions (MFEs).

First discovered by psychologist Paul Ekman in 1966, MFEs are brief, involuntary movements of the face that last less than half a second. Unlike typical expressions, MFEs are tied to the brain’s limbic system and hard to control, said Shaun.

Here are seven major emotions and their associated muscle movements:

- Fear: Widened eyes, raised eyebrows, and a tense facial expression.

- Anger: Furrowed brows, tightened lips, and flared nostrils.

- Sadness: Downturned lips, drooping eyelids, and a furrowed brow.

- Happiness: Upturned lips, crow's feet around the eyes, and relaxed facial muscles.

- Surprise: Raised eyebrows, widened eyes, and an open mouth.

- Disgust: Wrinkled nose, raised upper lip, and a slight shake of the head.

- Contempt: One side of the mouth raised, often accompanied by a sideways glance.

According to Shaun, at least one of these muscle movements will be exhibited – even if it’s just for a split second – when a person feels a particular emotion. This will always be the case regardless of how hard they try to control their emotions.

In other words, our bodies will never lie.

Identifying MFEs

To spot these fleeting micro-expressions, HTX’s B&P CoE is currently developing a software with the aid of AI or, more specifically, facial recognition machine learning algorithms.

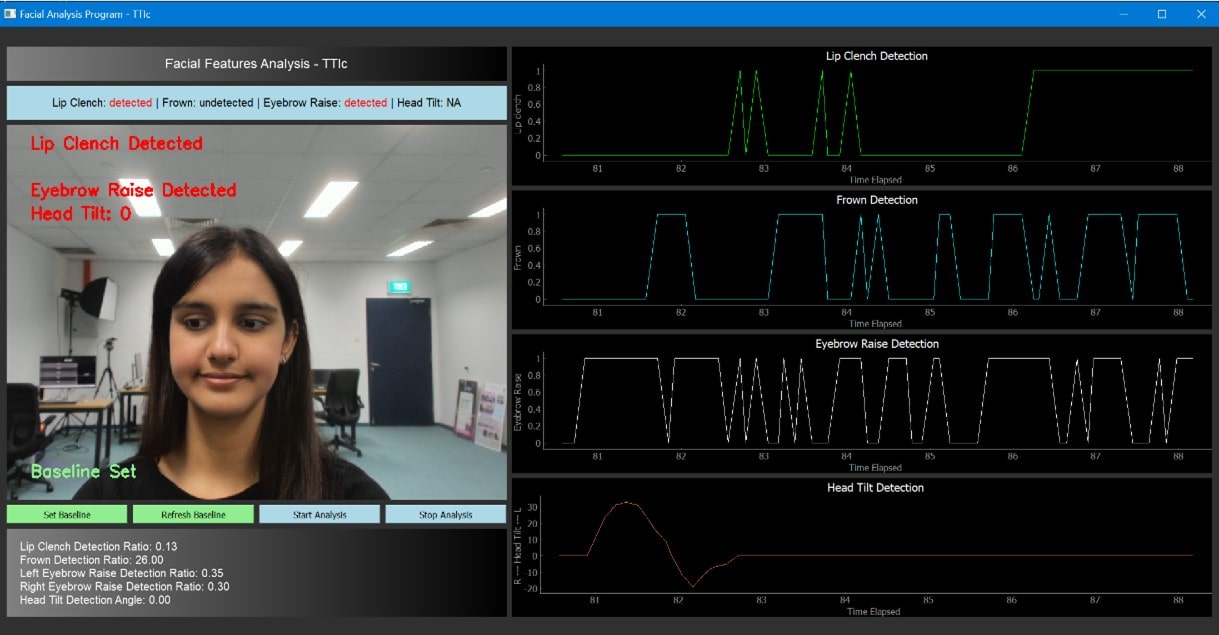

What this software does is analyse footage from a camera to determine if a person displays any MFEs during an interview.

Developing this piece of innovation, said Shaun, is a painstaking process.

First, the team uses the open-source library called Mediapipe to identify and superimpose 468 facial landmarks onto a person’s face. These landmarks are used to track the movement of facial features.

Facial landmarks (Photo: HTX)

The team then studies the interactions between these facial landmarks when a person exhibits MFEs. For example, when a person frowns briefly, the distance between the inner brows decreases.

Shaun said it is also necessary to determine which facial landmarks around the inner brow area exhibit consistent change in distance between each other whenever a person frowns. This ensures that the MFE can be picked up across different faces.

Once the main landmarks associated with the corresponding MFE have been identified, the team then develops an algorithm to track these detections.

A glimpse of the MFE detection software interface. (Photo: HTX)

Advantages

This MFE detection tool would be especially useful as investigators could miss fleeting micro-expressions during interview sessions.

Another advantage it has is it does not require the operator to undergo prior training. The operator of a polygraph, on the other hand, needs to undergo several months of training.

Furthermore, the MFE detector is contactless and does not require subjects to wear sensors on their bodies, unlike the polygraph.

But just like the polygraph, the MFE detector won’t be able to provide a definitive answer to whether someone is lying, said Shaun.

“This new tool could be used in conjunction with the polygraph to give investigators an even better idea of what someone is feeling,” he said.

“But it is the investigators who have to decide if a person is lying, and they can better determine this by asking the right questions. Ultimately, the task of deception detection is both a science and an art!”